Memoir of Sexual Assault Survivor Chanel Miller Sparks Awareness, Empathy, Anger and Engagement

Memoir of Sexual Assault Survivor Chanel Miller Sparks Awareness, Empathy, Anger and Engagement

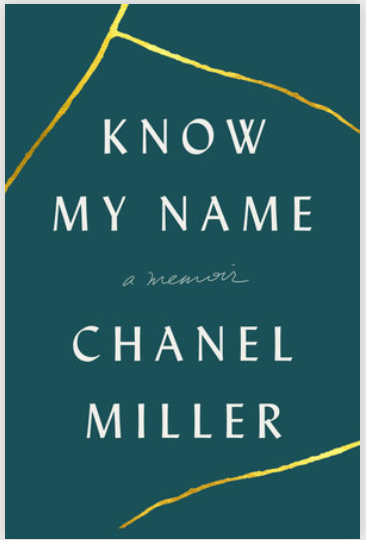

This spring, four UWS students from Dr. Kenna Bolton Holz’ “Gender, Psychology & Society” class were completing service-learning hours with CASDA to support Sexual Assault Awareness Month (SAAM) activities on campus. When Covid-19 restrictions prevented the previously planned events from taking place, these students were assigned a new SAAM project: to read Chanel Miller’s recent memoir, “Know My Name,” and reflect on her experiences. The students discussed the book in a virtual session and then shared their reflections with CASDA. Chanel’s story made an impact on these students. As one of them noted, “we wished that everyone in our class got to read the book.” Thank you to all four students for your insight and follow-through!

We are pleased to publish the entirety of student Rachel Hotakainen‘s book review here on our website, preceded by excerpts from the other three students’ reflections. Sexual Assault Awareness Month lasts for one more week, but whether it’s during April or another month, we hope that you are moved to seek a copy of “Know My Name” and read it yourself!  “The whole time no one told her what had happened to her…If someone has just been sexually assaulted, the person should have all the information right away, not finding out later on the news.” Hadeel Huwaish

“The whole time no one told her what had happened to her…If someone has just been sexually assaulted, the person should have all the information right away, not finding out later on the news.” Hadeel Huwaish

“When she was asked if she should press charges, she said yes, but when saying yes, she didn’t know what that meant.” Hadeel Huwaish

“What is wrong is that a female has to worry about everything she does because of what could happen to her.” Hadeel Huwaish

“She had to put her life on hold… After all, she couldn’t handle it.” Hadeel Huwaish

“Our system needs to change for victims to make sure they have everything they need for their voice to be heard.” Hadeel Huwaish

“This memoir was really eye opening to me, especially when it came to the aspects of the system that affected Chanel, as I am sure it affects so many other victims too.” Kylie McGuire

“They made it sound like this was a burden in (the perpetrator’s) life without thinking about who really has to carry the weight of this incident around with them everyday, and that is Chanel.” Kylie McGuire

“…what I do know from reading this is that Chanel was strong. She went through almost four years of this trial to make sure she would get some kind of conviction and be able to say everything she wanted to say, unlike the night of her attack, when she was unable to say anything at all. She got to stand up for herself even when people made it so difficult by tearing her down constantly and manipulating what she said.” Kylie McGuire

“Know My Name by Chanel Miller is a testament, not only to the emotional horrors of being sexually assaulted, or the horrors of a legal system that is set up against victims of sexual assault, but also to the incredible hope and strength of women working together towards change.” Madeline Witt

“This developing relationship between strong women demanding change gives the reader a longing hope for future change, future support, and a future where sexual assault is not a normality of society.” Madeline Witt

“Chanel Miller’s writing is not simply a narration, rather a friend lending quiet support. A voice that urges you to fight back. A voice that tells you, “You are not alone. You never have been.” A woman standing up and stating that what happened to her, and what has happened to millions of other women, is wrong and cannot be treated as a normal event. Walking with keys between fingers, pretending to talk on the phone, crossing the dark street at the sight of a man, hands covering drinks, and having to rely on the kindness and bravery of strangers to protect you should not be normal. Yet, I do not know a single woman who has not done everything in that list to protect themselves, but women are still being assaulted. Which urges an important question, does it really matter how much she drank? What she was wearing? Who she is dating? Rather: Why did he think that was okay? Why didn’t he stop?” Madeline Witt

Chanel Miller: Learn. Her. Name.

by Rachel Hotakainen

After reading “Know My Name” by Chanel Miller, I can tell you this: if you haven’t read the book, read it. The words that leapt off the pages were beautifully haunting, and I read on in awe, making sure to take in the importance of the messages held in each and every sentence. “Know My Name” is Chanel’s memoir, which eloquently tells her story of sexual assault and everything that came along with it: from the graphic assault, to the torturous legal proceedings, and every emotion she struggled with along the way. She also makes it alarmingly clear that this wasn’t just a singular issue, but a societal pattern, one that’s gone too far and has hurt too many people. We let things like this happen every day while turning a blind eye, simply because we’re too uncomfortable with the topic to have a conversation that needs to be had.

So, let’s talk about it. We live in a society where everyone feels that their opinion is the right one, but when it comes to sexual assault and rape, there should only be one option: believe survivors. Listen to their stories, and then offer your support. It was appalling to read everything Chanel went through. As if being sexually assaulted wasn’t already enough to bear, Chanel was attacked by the media, let down by the justice system, and trapped within her fear. But what was most disturbing was how the assault was handled by the people we put faith in to be there for us. The police reports, witness statements and even perpetrator Brock Turner’s own words painted a clear picture that something was horribly wrong, yet the entire world was trying to downplay her assault as just another college hookup. The media depicted Brock as the victim, losing a swimming scholarship and his reputation, and hundreds of people blindly believed the articles, and began to harass Chanel, taking part in a disgusting societal trend of victim-blaming.

How is it that we continue to take part in conversations where we shame the victim for being drunk or accuse her of lying for money, fame, or attention? Chanel was above the legal drinking age of 21. Getting drunk and going out partying is considered socially acceptable and perfectly normal, and even gains you popularity. But somehow, being raped while drunk is simply considered a bad judgement call on the victim’s part. Why are we telling women to cover up or travel in packs? Why can’t we just establish a simple truth: don’t rape people. If you don’t have consent, don’t do it.

Unfortunately, this is a small part of a much larger societal issue of a toxic rape culture that pressures most victims of sexual assault and rape to stay quiet over a valid fear of not being believed or of being blamed and torn apart for their part in it. But think about it, as a society, we don’t do this for any other crime. As Miller says herself, “what was unique about this crime, was that the perpetrator could suggest the victim experienced pleasure and people wouldn’t bat an eye. There’s no such thing as a good stabbing or bad stabbing, consensual murder or non-consensual murder. In this crime, pain could be disguised and confused as pleasure.” And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. She continues to explain this by saying, “in rape cases, it’s strange to me when people say, Well why didn’t you fight him? If you woke up to a robber in your home, saw him taking your stuff, people wouldn’t ask, Well why didn’t you fight him? Why didn’t you tell him no? He’s already violating an unspoken rule, why would he suddenly decide to adhere to reason? What would give you reason to think he’d stop if you told him to? And in this case, with my being unconscious, why were there still so many questions?”

I was shocked to read this, and it made me see our society in a whole new light. Why aren’t we talking about this? If we gave sexual violence even a fraction of the attention we’re giving COVID-19, we could’ve helped so many women before they became victims. So please, do your part. Spread awareness. Talk about it. If you see something, say something. Check in on your friends. And most importantly, believe them when they tell you their story. Don’t victim blame and feed into rape culture. Break the pattern. Shut up and listen and then offer your support. We can change this toxic rape culture that has infected our society, all we have to do is try.

Included at the end of Rachel’s Essay:

25 Most Powerful Excerpts from “Know My Name” that Everyone Should Read

“I didn’t know that money could make the cell doors swing open. I didn’t know that if a woman was drunk when the violence occurred, she wouldn’t be taken seriously. I didn’t know that if he was drunk when the violence occurred, people would offer him sympathy. I didn’t know that my loss of memory would become his opportunity. I didn’t know that being a victim was synonymous with not being believed.”

“The only chance he had of being acquitted was to prove that to his knowledge, the sexual act was consensual. He’d force moans in my throat, assign lecherous behavior, to shift the blame onto me.”

“It bothered me that having a boyfriend and being assaulted should be related, as if I, alone, was not enough. … What if you’re assaulted and you didn’t already belong to a male? Was having a boyfriend the only was to have your autonomy respected? Later I’d read suggestions that I cried rape because I was ashamed I had cheated on my boyfriend. Somehow the victim never wins.”

“I understood what the woman meant, that a transaction as simple as receiving a piece of furniture from a stranger possessed an inherent threat, that anytime we met someone online we must scan for signs of assault, rape, death, etc. We knew this. But the guy did not speak this language, he just saw a desk.”

“When a woman is assaulted, one of the first questions people ask is, Did you say no? This question assumes that the answer was always yes, and that it is her job to revoke the agreement. To defuse the bomb she was given. But why are they allowed to touch us until we physically fight them off? Why is the door open until we have to slam it shut?”

“Trauma was refusing to adhere to any schedule, didn’t seem to align itself with time. Some days it was as distant as a star and other days it could wholly engulf me.”

“You have to hold out to see how your life unfolds, because it is most likely beyond what you can imagine. It is not a question of if you will survive this, but what beautiful things await you when you do.”

“In the beginning, I thought this would be easy. The first time I was told Brock had hired a prominent, high-paid attorney I thought, Oh, no. And then I thought, So? Even he could not change the truth. The way I saw it, my side was going to convince the jury that the big yellow thing in the sky is the sun. His side had to convince the jury that it’s an egg yolk. Even the most eminent attorney would not be able to change the fact that it is a massive, blazing star, not a ludicrous floating egg. But I had yet to understand the system. If you pay enough money, if you say the right things, if you take enough time to weaken and dilute the truth, the sun could slowly begin to look like an egg. Not only was this possible, it happens all the time.”

“My DA would later tell me that women aren’t preferred on juries of rape cases because they’re likely to resist empathizing with the victim, insisting there must be something wrong with her because that would never happen to me. I thought of mothers who had commented, My daughters would never … which made me sad because comments like that did not make her daughter any safer, just ensured that if the daughter was raped, she’d likely have one less person to go to.”

“You want the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth? Your whole answer was sitting with his shoulders low, head down, his neatly cut hair. You want to know why my whole goddamn family was hurting, why I lost my job, why I had four digits in my bank account, why my sister was missing school? It was because on a cool January evening, I went out, while that guy, that guy there, had decided that yes or no, moving or motionless, he wanted to fuck someone, intended to fuck someone, and it happened to be me. This did not make me deficient. This did not make me inadequate.”

“Victims are often, automatically, accused of lying. But when a perpetrator is exposed for lying, the stigma doesn’t stick. Why is it that we’re vary of victims making false accusations, but rarely consider how many men have blatantly lied about, downplayed, or manipulated others to cover their own actions?”

“The rules of court would not necessarily protect me; swearing under oath was just a made-up promise. Honesty was for children. Brock would say and do what he needed; unabashedly self-righteous. He had given himself permission to enter me again, this time stuffing words into my mouth. He made me his real-life ventriloquist doll, put his hands inside me and made me speak.”

“During the trial, the jury was forced to pick; is he wholesome or monstrous. But I never questioned that any of what they said about him was true. In fact I need you to know it was all true. The friendly guy who helps you move and assists senior citizens in the pool is the same guy who assaulted me. One person can be capable of both. Society often fails to wrap its head around the fact that these truths often coexist, they are not mutually exclusive. Bad qualities can hide inside a good person. That’s the terrifying part.”

“We’re not after you, we’re after what you did, and now we are here to hold you accountable.”

“They tell you that if you’re assaulted, there’s a kingdom, a courthouse, high up on a mountain where justice can be found. Most victims are turned away at the base of the mountain, told they don’t have enough evidence to make the journey. Some victims sacrifice everything to make the climb, but are slain along the way, the burden of proof impossibly high. I set off, accompanied by a strong team, who helped carry the weight, until I made it, the summit, the place few victims reached, the promised land. We’d gotten an arrest, a guilty verdict, the small percentage that gets the conviction. It was time to see what justice looked like. We threw open the doors, and there was nothing.”

“The judge had given Brock something that would never be extended to me: empathy. My pain was never more valuable than his potential.”

“Before I was living in real time. Now I evaluate the moment before I can move into it. I am always asking permission, anticipating having to present myself to an invisible jury, answering questions before a defense. When I reach for a piece of clothing, the first thing I think is, What will they think if I wear this? When I go anywhere I think, Will I be able to explain why I am going? If I post a photo I think, If this were submitted as evidence, would I look too silly, my shoulders too bare? The time I spend questioning what I’m doing, turning things over and talking myself back to normalcy, has become the toll.”

“I told myself, don’t become them. Focus on who you want to be. I fought hard rewriting drafts of this book to dial down the sarcasm, personal attacks. I vowed not to minimize or dehumanize. The goal should never be to insult, it should only be to teach, to expose larger issues so that we may learn something. I want to remain me. So I use my strength not to shove back, but to exercise my voice with control. … For every person that wants to hurt me, there are more who want to help. I wish there had been a predatory expert, victim expert, consent expert to better educate the jury. We scrutinized the victim’s actions, instead of examining the behavioral patterns of sexual predators. How alcohol works to the predator’s advantage, to lower resistance, weaken the limbs.”

“I did not mind, this is not proof that he is bad, I am not here to judge his drug consumption. Rip that bong, boy. You can eat mushrooms for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. You can dab your heart out whatever the literal hell that means. You know why? Because it’s your life and you are free to consume as you please. But what you cannot to is come into my courtroom with the statement, I was an inexperienced drinker and party-goer, so I just accepted these things that [the guys on the swim team] showed me as normal … I’ve been shattered by the party culture and risk-taking behavior that I briefly experienced in my four months at school.”

“If students can be swiftly expelled for plagiarism or dealing drugs, the same punishment should be inflicted if there’s enough evidence to suggest they pose a threat to others. Oh but his reputation! That’s where he really suffers. My advice is, if he’s worried about his reputation, don’t rape anyone.”

“When you say go to the police what do you envision? I was grateful for my team. But the police will move on to other cases while the victim is left in the agonizing, protracted judicial process, where she will be made to question, and then forget, who she is. You were just physically attacked? Here’s some information on how you can enter a multiyear process of verbal abuse. Often it seems easier to suffer rape alone, than face the dismembering that comes with seeking support.”

“When society questions a victim’s reluctance to report, I will be here to remind you that you ask us to sacrifice our sanity to fight outdated structures that were designed to keep us down. … This is not about the victim’s lack of effort. This is about society’s failure to have systems in place in which victims feel there’s a probable chance of achieving safety, justice, and restoration, rather than being re-traumatized, publicly shamed, psychologically tormented, and verbally mauled. The real question we need to be asking is not, Why didn’t she report, the question is, Why would you?”

“Each time a survivor resurfaced, people were quick to say what does she want, why did it take her so long, why now, why not then, why not faster. But damage does not stick to deadlines. If she emerges, why don’t we ask her how it was possible she lived with that hurt so long, ask who taught her never to uncover it.”

“There have been numerous times I have not brought up my case because I do not want to upset anybody or spoil the mood. Because I want to preserve your comfort. Because I have been told that what I have to say is too dark, too upsetting, too targeting, too triggering, let’s tone it down. You will find society asking you for the happy ending, saying come back when you’re better, when what you say can make us feel good, when you have something more uplifting, affirming. This ugliness was something I never asked for, it was dropped on me, and for a long time I worried it made me ugly too.”

“Denying darkness does not bring anyone closer to the light. When you hear a story about rape, all the graphic and unsettling details, resist the instinct to turn away; instead, look closer, because beneath the gore and police reports is a whole, beautiful person, looking for ways to be in the world again.”